In the annals of Roman history, few emperors capture the imagination quite like Nero. Renowned for his eccentricities and notorious reign, Nero’s legacy teeters between the fascinating and the grotesque. As we delve into the imperial and mad aspects of this infamous ruler, we invite you to consider: what constitutes the line between brilliance and madness in leadership? Perhaps some of the behaviors exhibited by Nero were less about insanity and more about the burdens of absolute power. Here, we uncover three intriguing and somewhat outlandish facts about Nero that embody both the imperial and the mad.

1. Extravagant Performances: The Theatrical Emperor

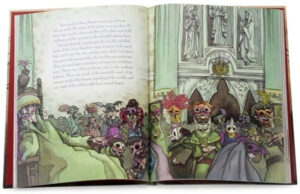

Nero is often remembered for his grandiose performances in front of raucous audiences, thrusting himself into the limelight not just as a ruler, but as a performer. Imagine the emperor of Rome, adorned in elaborate costumes, strutting the stage with the fervor of a seasoned actor. Nero reveled in the arts—he participated in chariot races, musical competitions, and dramatic performances, much to the chagrin of the Roman elite who believed such pastimes were beneath his dignity.

His most famous performances were in the Greek city-states, where he was met with fervent adulation from audiences entranced by the spectacle. Many historians argue that his pursuit of artistic fame was not merely a personal indulgence; it was a calculated ploy for public approval. After all, what better way to win the hearts of the populace than to showcase his talents and entertain the masses? However, this propensity for public performance did not come without controversy. During one infamous incident, he ordered that the Olympic Games be postponed for a year so that he could compete, and unsurprisingly, he emerged victorious in multiple events, albeit not without critics claiming that he had tilted the scale of fair competition.

2. The Great Fire of Rome: Blame and Bizarre Actions

Perhaps one of the most dreadful incidents during Nero’s reign was the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, an event that devastated much of the city. While the true cause of the fire is shrouded in ambiguity, whispers circulated that Nero himself had ordered the conflagration to clear land for his grand architectural project: the Domus Aurea, a lavish palace that would later symbolize the emperor’s opulence. The rumor mill churned furiously, suggesting that his ties to the catastrophe might have been deeper than mere speculation.

In a bizarre twist, rather than expressing remorse or taking decisive action to aid the suffering populace, Nero opted for theatrics, allegedly composing a poem about the destruction while strumming a lyre. In the face of a city ablaze, his indifference intensified public scrutiny and skepticism. Although he provided temporary shelter for the displaced and initiated rebuilding efforts, these gestures were often perceived as feeble attempts to absolve himself of suspicion. Interestingly, his handling of the crisis not only reflected a strangely narcissistic approach to governance but also a profound misunderstanding of the expectations the Roman people placed upon their emperor. Did his artistic inclinations prevent him from recognizing the gravity of his leadership role?

3. Persecutions and Paranoia: The Mad Overtones

As his reign advanced, so did a palpable paranoia that seeped into every aspect of Nero’s rule. Fearful of conspiracies and potential usurpers, Nero enforced a reign of terror, initiating brutal purges against those he suspected of betrayal. One of the most notable victims was his own mother, Agrippina, whom he had executed to eliminate any threat to his power. The depths of his madness ran perilously deep, as this act was an illustration of his delusional obsession with control and dominance.

What stands out starkly in this chaotic narrative is Nero’s decision to scapegoat the Christians for the Great Fire. This marked the inception of organized persecution against Christians in Rome, wherein they faced horrific tortures and executions in hideous public spectacles. Such actions reveal the duality of Nero’s character; he oscillated between the whimsical artist and the tyrannical ruler. His apparent delight in the spectacle of these tortures solidified his transition from merely eccentric to deeply unhinged. Could it be that in his quest for artistic expression, he lost touch with the very humanity he was meant to govern?

As we conclude our exploration of Emperor Nero, it’s evident that history weaves a complex tapestry of imperial grandeur and psychological unrest. Nero’s penchant for extravagance clouds his political acumen, transforming him into a figure of both admiration and ridicule. He intrigues us, representing the thin veils separating madness from creativity, tyranny from charisma.

How does one accurately assess a character such as Nero? Was he a misunderstood artist swallowed by the enormity of leadership, or a cunning tyrant willing to sacrifice anyone for the sake of his own ambition? This ambiguity continues to ignite debates among scholars and enthusiasts alike. In the end, Nero’s legacy serves as a colorful reminder of the profound complexities that define the human experience—especially when the stakes of absolute power are at play.